An SBIC Increases The Odds Of Black-Owned Businesses Receiving Private Equity

Media Outlet

Geri Stengel

The Enterprise Center (TEC) is blazing a trail with its $50 million Innovative Capital Growth Fund, demonstrating how private sector investment can be leveraged through the Small Business Administration's (SBA) Small Business Invest Companies (SBIC) program to increase private-equity investment in Black-owned businesses.

In 2021, minority-owned firms managed a minuscule 1.4% of all assets while representing about 40% of the population. SBICs with at least one person of color on the investment team were more than twice as likely than all-white SBICs to make investments in companies whose CEO was a person of color. The same was true for women. SBICs are a program of the SBA Office of Investment and Innovation.

The Fund will provide much-needed capital, allowing Black-owned businesses to grow, hire people, develop innovative products or services, and acquire other companies. It will help create a diverse private equity industry reflective of the U.S. population.

Leading the Change for Equitable Equity

Because we [TEC] are in Philadelphia, the majority of minorities that we help are African Americans, [by far] the largest minority population," said Della Clark, president at The Enterprise Center and Partner at Innovate Capital Growth Fund.

As a Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA) Business Center, one of TEC's focuses is connecting minority- and women-owned businesses to government and corporate contract opportunities through supplier-diversity programs. With both a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) and SBIC under one roof, it is uniquely positioned to help early-stage and mature growth-oriented companies.

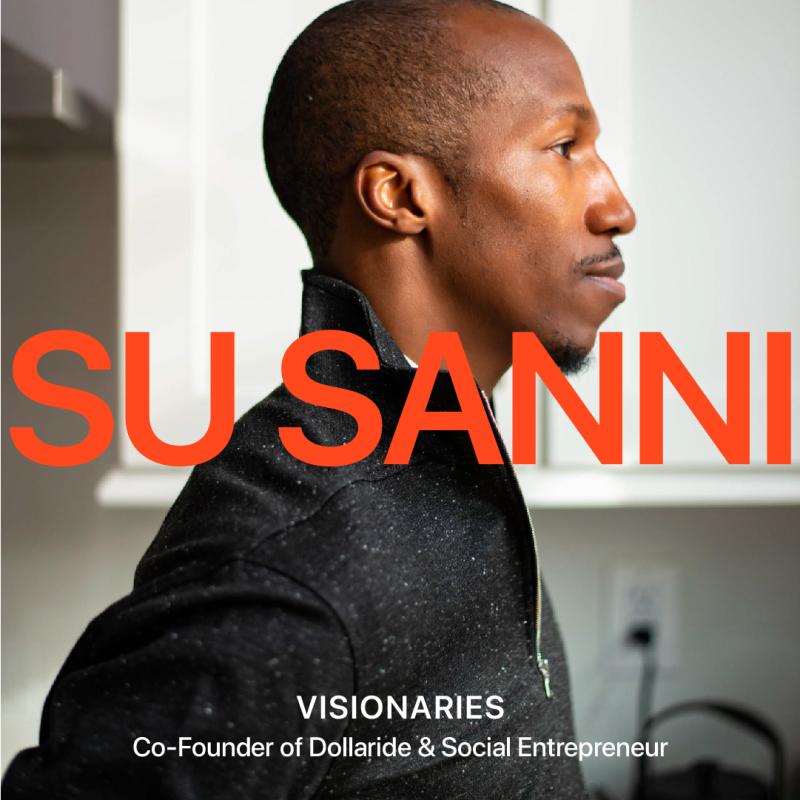

Innovate Capital targets minority- and women-owned businesses in the Mid-Atlantic region with revenues between $2 million and $20 million that have recurring contracts in sectors such as education, healthcare, infrastructure, manufacturing, technology/software, and value-added distribution. It is particularly focused on companies serving educational and medical institutions, which are the economic drivers in the region and offer large-dollar, five-year contracts.

Sizing the Funding Gap

For every $1 of wealth that the average white family has, a Black family has 12.5 cents, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Dramatically lower wealth means that when would-be Black entrepreneurs want to start a business, they have much less of their own money to invest in it, limiting their ability to grow their businesses.

Black startup entrepreneurs are less likely to receive loans and more likely to rely on more expensive credit card debt than their white counterparts, according to Startup Financing Trends by Race: How Access to Capital Impacts Profitability. They are more likely to be rejected and pay higher rates, according to Disparities in Capital Access between Minority and Non-Minority-Owned Businesses: The Troubling Reality of Capital Limitations Faced by MBEs. Lower levels also dampen the rate at which Black men and women start businesses compared to their white counterparts.

"When you look at the difference between a founder or CEO from a low-wealth community, they historically get offered [technical assistance] programs and debt," Clark says. "A founder or CEO from a prosperous community starts with capital from family and friends; many receive money from angel investors, followed by venture capital.

"By the time they get to $5 million in revenue, they look attractive for mezzanine financing from banks or other institutional investors," said Clark. "Whereas minority-owned businesses' balance sheets are loaded up with debt when they get to $5 million in revenue." Interestingly, debt is most relied upon by entrepreneurs who have the greatest difficulty accessing it to start and expand their ventures.

"We have a flawed system. Funders give us money for programs with unrealistic metrics," said Clark. "They don't provide money for follow-on capital to that program." Nonprofits like TEC staff up, but the process starts again in two or three years when the program ends.

Leveling the Playing Field

Clark came to realize that low-wealth communities get program dollars, but prosperous communities get investment capital. CEOs and founders from prosperous communities have accelerated growth for their companies versus CEOs and founders from low-wealth communities whose companies experience slow growth.

The capital stack for companies whose CEOs and founders were from low-wealth communities was all or predominately debt. In contrast, the stack from prosperous communities had much more equity in the mix. The debt-to-equity ratio affects the balance sheet of minority businesses, making them unattractive to private equity investors or as an acquisition target.

"If we want to change poverty in Philadelphia, we will have to focus on wealth creation by identifying CEOs who are standouts and have growth IQ," - Della Clark

TEC determined that it needed to provide equity investments to companies with predictable income because they had contracts with local, state, and federal governments as well as corporations. These companies, in turn, would provide subcontracting opportunities to small minority- and women-owned businesses.

"That led us to pursue an SBIC license," Clark said.

Starting an SBIC was a good fit for TEC. As an MBDA Business Center, it receives federal funding to support minority-owned businesses with technical assistance, particularly for certified minority- and women- owned companies going after government and corporate contracts as part of supplier-diversity programs. It is also part of a federal lending program—CDFIs.

As a CDFI, TEC receives funding from banks as part of their obligations under the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). Banks are interested in investing in SBICs because it's one of the few ways they are allowed by law to invest directly in private-equity funds. These funds are considered riskier but promise higher returns than other investments. They can also use CRA dollars for the investment. TEC has pre-existing relationships with banks and other institutions that could be limited partners in an SBIC fund.

There are nearly 300 SBICs, and few are owned by women, minorities, and veterans—only 49. The SBA application fee is $45,000, and there are significant legal and other fees in setting up and managing a fund. "That's a lot of money, and many minority organizations do not have it," said Clark.

In February 2022, Innovative Capital Growth Fund received its license from the SBA. "We've closed on $20 million and have about $7 million in commitments," said Clark. Institutional investors in Innovate Capital include Bank of America, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Delaware Valley Regional Economic Development Fund, Forman Family Foundation, Halloran Philanthropies, Independence Blue Cross, Republic Bank, and the University of Pennsylvania.

Raising money has been slow going. "I didn't realize raising money was going to be difficult," said Clark. "Most large foundations and corporations would rather give nonprofits like ours grants versus investment capital."

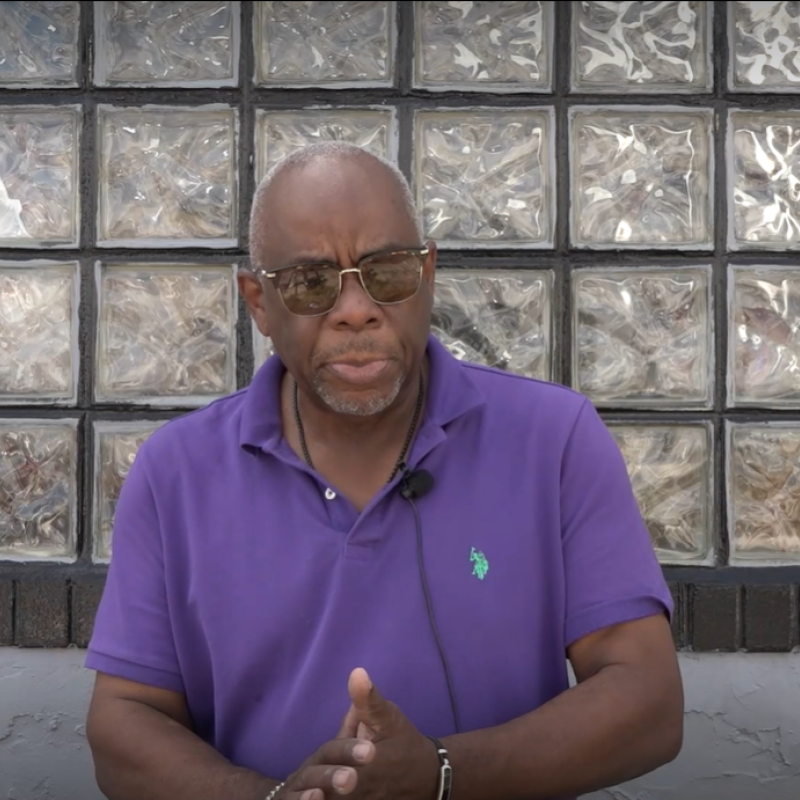

Clark serves as one of three managing partners. "I come from the CDFI world and don't have a Goldman Sachs pedigree," said Clark. Her two partners complement her skills. Bob Palmer is a former managing director of CMS Mezzanine and brings more than 30 years of experience in banking and private equity. Blessy Thomas is an experienced growth strategist.

The public-private investment vehicle is a win-win—it increases the odds of Black-owned businesses receiving private equity funding and provides private investors with the potential for high returns.

How will you take advantage of an existing source of capital—SBICs—being used in a novel way?