‘Where do we go from here?’: A look at Black Philadelphians’ economic state, decades after the March on Washington

Media Outlet

Jordan Levy

Sixty years since Martin Luther King Jr. shared his most famous address at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the majority of Black Philadelphians are still far from that dream.

A new report keyed to King’s milestone speech shows that nationwide, most economic aspirations of the Civil Rights Era have simply not come to pass.

“People of color are still behind, and progress has continued to be slow,” said Della Clark, president of The Enterprise Center, a West Philly economic development nonprofit. “I think that this country is not headed in the right direction, as it relates to cultural intelligence and Black and white in America.”

Economically speaking, Black America’s reality veers much closer to MLK’s 1967 confession that aspects of his dream had “turned into a nightmare.”

Titled “Still a Dream: Over 500 Years to Black Economic Equality,” the new report crunched some numbers and determined it would take 513 years for Black households in the U.S. to achieve income equality with white households at the current rate of change.

That income disparity is obvious in Philadelphia. The city’s overall median income in 2021 was just under $53,000. But that figure changes dramatically if you split residents by race. The median for white, non-Hispanic households was around $74,000, nearly double the median Black household income of $39,000.

“Still a Dream” adds that the road to wealth equality — when the median value of financial assets is the same between Black and white households — is a disheartening 780 years long.

The report notes that there have been improvements Black educational attainment since 1963: the national Black four-year high school graduation rate is 90.1%. In the Philly School district, however, only 79.6% of Black students finish high school in four years.

When it comes to homeownership, the city’s Black-white gap is slimmer than the national gap, which is worse today than in 1960, per the “Dream” report.

However, Black homeownership in Philadelphia has long been better than the national average for Black households. The local racial gap has shrunk since the 60s because of how white homeownership in Philly is falling, not because more Black families have access to mortgage credit needed to buy homes.

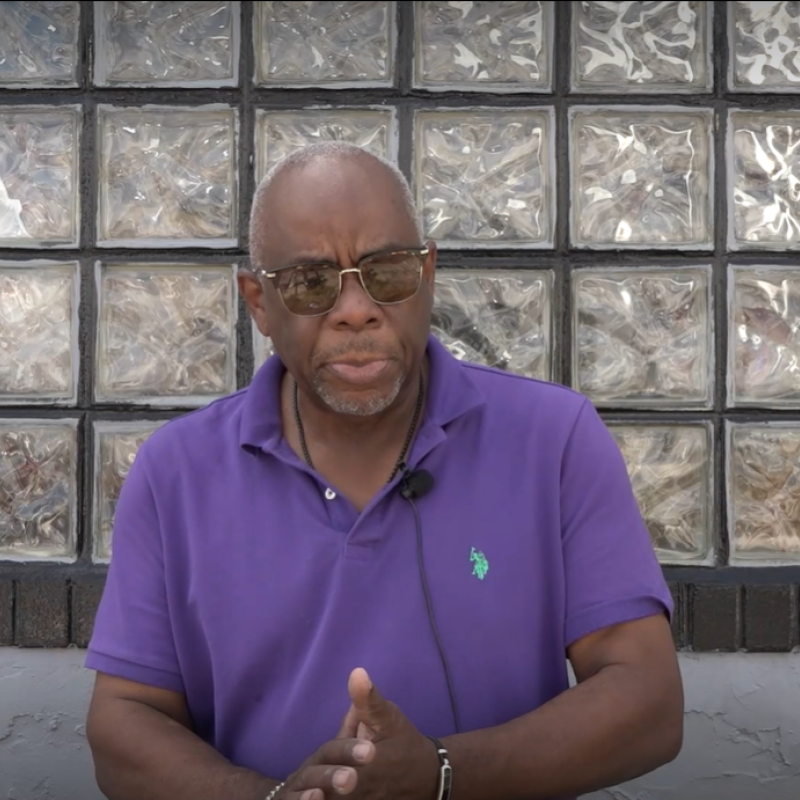

These national and local realities raise sobering questions for Richard Hooker Jr., Secretary Treasurer and Principal Officer for Teamsters Local 623, which represents over 6,000 workers in Philadelphia.

“It kind of gets you to wonder, are we ever going to catch up?” Hooker said. “And if we are going to catch up, what is the process to ensure that we do?”

Like improving educational attainment and lowering unemployment, increasing Black union leadership was seen by many 1960s civil rights activists as key to transforming economic conditions. That’s recently begun to happen in Philly.

It can still be a part of the solution, Hooker said — but only if there’s a concerted effort to change the way business is done.

“I think the piece that we’re missing,” Hooker said, “is what would happen if myself, Ernest Garrett, Jerry Jordan, Ryan Boyer, if we all got together and really started pushing an agenda that was inclusive for everybody.”

A startling disparity in Philadelphia is seen in who owns and operates a business in the city.

Only 2.5% of Philly businesses with employees are owned by Black people, per 2016 Census data. Add in sole proprietorships, businesses without any employees, and the count rises to 25% Black-owned.

That shows up in how Philly’s public contracts get awarded. In fiscal year 2021, roughly 80% went to firms owned by white men, with the rest split among firms owned by women (WBE) and people of color (MBE). That’s a worse imbalance than five years ago — and may partly have to do with availability.

For example, a recent report crafted to help the city set feasible diversity goals found few Black-owned firms offering single-family, multifamily, and commercial construction — 0%, 0.61%, and 0.16% of the local industries, respectively.

This is something The Enterprise Center, in West Philly, is trying to address. “Closing the contract gap, the capital gap, the expertise gap, is at the forefront of the Enterprise’s work,” said Clark.

But it takes more than just telling people to “start a business,” she said. There are too many training programs for Black entrepreneurs, Clark argued, when what they really need is direct access to capital.

Marcia Chatelain, professor of Africana studies at Penn, explored McDonald’s surprising success in providing access to Black entrepreneurs in her Pulitzer Prize-winning book “Franchise.”

Turns out McDonald’s so-called “success” was only relative compared with other attempts at “Black capitalism” — i.e., the federal and local programs designed to (at least appear to) boost Black commercial efforts. Those efforts continue to miss the mark, per Chatelain.

The popular call to “buy Black” or support local businesses can’t be “the sole or primary solution” to these economic conditions, Chatelain said, even as the idea is encouraged by corporations and Black celebrities.

The narrative behind that, she said, is “if your community is failing it’s because local people aren’t supporting it enough. When the reality is that the federal government is not funding and creating avenues for its success.”

Clark, of The Enterprise Center, says there are opportunities to move the needle through the plethora of federal contracts coming online thanks to Biden administration projects on infrastructure and domestic tech manufacturing.

“The question is,” Clark asked, “are the state and city ready to flow some of these opportunities down to lift up [those in] poverty?”

As for Hooker of the Teamsters, he believes increased and increasingly militant activism is needed to chip away at these disparities at a faster rate.

“I think we need to march not only on D.C., but we need to march to Harrisburg, in Philadelphia, to every city hall to talk about these issues,” Hooker said. “If this thing prolongs for another 60 years, I don’t think our young people are going to take that.”